America now has more Republicans than Democrats

The end of an almost-century long era

Something very unusual by historic standards happened in this year’s election: there were lots more Republicans than Democrats in the electorate.

After the exit polls were reweighted to reflect the final popular vote result, Republicans outnumbered Democrats by 5 points in the AP VoteCast survey and by 4 points in the network exit polls.

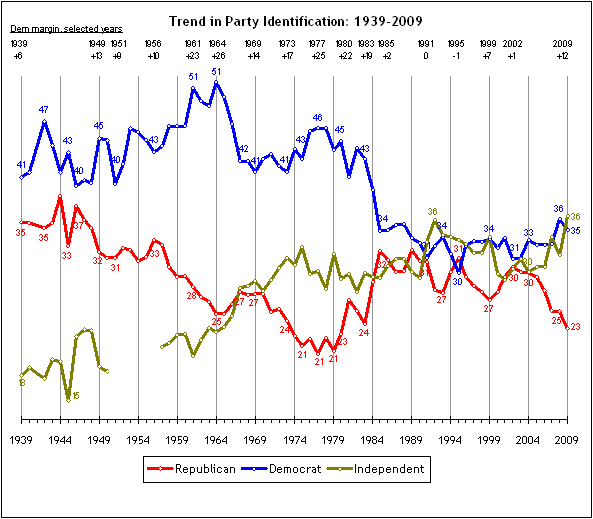

Historically, this is practically unheard of. Democrats have held a longstanding advantage in party identification that dates back to the New Deal, with Republicans drawing even on only a couple of occasions — the 1994 Republican Revolution and the immediate post-9/11 period.

Until Ronald Reagan remade the Republican Party’s image in the 1980s, Democrats held a massive advantage in party ID that often reached 2-to-1 in the 1960s and ‘70s. Only after Reagan’s 1984 landslide did the modern narrow Democratic advantage take hold, where it’s stayed for the most part ever since.