How Selzer (or anyone else) can get an election wrong

Reweighting my own polls exactly like that last Iowa poll to show you what happened and spilling my guts on the state of the polling industry

The polls missed, underestimating Donald Trump for a third election in a row, but they did not miss as much as the 2016 and 2020 polls, and got important things right: the realignment of nonwhite voters, Democrats’ problems with younger voters and being somewhat okay with older voters, and the fact that Donald Trump was more popular this time in a way that probably made him a slight favorite.

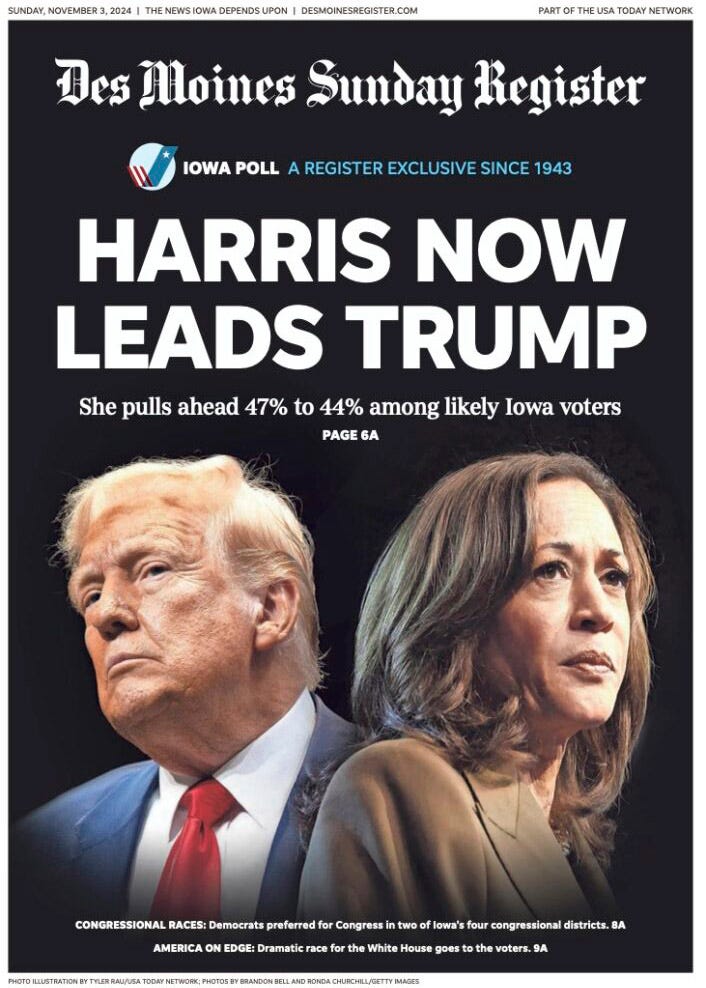

Some polls missed more than others, none more notably than the final Selzer poll in Iowa that put Kamala Harris up 3 points. The actual result in the Hawkeye State was 13 points—in Trump’s direction.

The whole Selzer episode is illustrative of a lot of things in the polling methodology debate that get rehashed interminably before the election—but which invariably get dropped after the election, because everyone has shifted to talking about the actual result.

But after the election is exactly the right time to grade the polls, not just on whether they hit the mark on the overall margin, but on how well certain methodologies did. Pre-election, there’s a tendency to treat all polls with equal validity, and then discriminate on the basis of individual pollsters’ reputation (e.g. “gold standard” polls like NYT/Siena, Marquette Law, or Selzer, vs. “red wave”/”flood the averages” pollsters like Trafalgar or Insider Advantage). There’s little attention paid after the fact to the methodological decisions each makes and how this contributes to their overall level of accuracy or what’s going on under the hood in the crosstabs.

Ann Selzer’s poll don’t weight on very much: just age, sex, and region, and it only counts those who self report they are certain to vote as likely voters. This was the election when this always-questionable approach finally caught up with her. I am amazed it didn’t sooner. And on reflection, her home base of Iowa probably made it possible for these old-school methods to work for as long as they did: it’s a demographically homogeneous state high in social trust. This approach would have stopped working long ago in a diverse state with big divides between urban and rural areas and high-turnout white and low-turnout minority voters, where getting these mixes exactly right matters a lot.

Because Selzer picked up trends others hadn’t, her poll was imbued with a quasi-religious level of significance. This runs against all that we’ve learned about just taking the average and focusing on the story that the polls collectively are telling, rather than valorizing any one individual pollster. But politicos were always willing to break this rule for Selzer out of superstituous belief.

Even the best pollsters have a bad poll, but just dismissing this as random error is a mistake. Certain methodological choices make outlier results more likely. These choices should be discussed and hashed out publicly outside the immediate pre-election period. And there are clear lessons to be learned based on comparing the results to the pre-election polls.