If AI is like the Internet, it won’t cost jobs

Debunking the AI jobs loss myth, islands of urban Trumpism, work-from-home babies and the cure for too much screen time

No. 391 | February 13, 2026

🤖 If AI is like the Internet, it won’t cost jobs

My early career built on being the first in Republican politics to ride the wave of digital transformation. And “first” is hardly an exaggeration. In the late 1990s, I built political websites and a proto-blog completely for fun and love of the game. This eventually got noticed and led to early jobs at the RNC and the George W. Bush campaign in 2004, where I started out as one of just two staffers running email and the website. Back then, the number of people in the GOP with this mix of skills could be counted by finger on one hand. I didn’t feel any real competition in the field until the late aughts — more than a decade after I coded my first website in 1995. A few years later, employment in the digital field skyrocketed — with hundreds of staffers on presidential campaigns doing the work of a handful of us in 2004.

The current moment with AI feels like the takeoff moment the Internet had in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Thinking about it, the degree of excitement I feel about AI today matches what I felt when I first got access to the web in high school.

Just because something is exciting, that doesn’t mean there aren’t parts of it that are terrifying — something I’m reminded of by watching downhill skiing at the Olympics. And there’s been a lot of focus on the “terrifying” part lately: the idea of AI getting so good that it’ll eventually replace white collar jobs en masse.

It’s not like we haven’t witnessed similar technology disruptions, though. Our current age has been defined by them. And our recent experience with the rise of the Internet and social media can provide some helpful guideposts for whether these predictions of doom will come true or not.

The Internet also should have shrunk the job market

In 2012, Facebook acquired Instagram for about $1 billion. At the time, Instagram had but a dozen employees. That kind of value creation by so few people looks like the darkest version of the automation story — technology concentrating wealth in a handful of operators while eliminating the need for everyone else. Massive digital networks where people buy advertising programmatically should, in theory, have rendered the ad sales forces of the Mad Men era obsolete. By the logic of today’s AI doomers, the first wave of digital transformation should have caused massive job loss.

It didn’t. And the reasons it didn’t are worth understanding, because they tell us a lot about the prospects for AI.

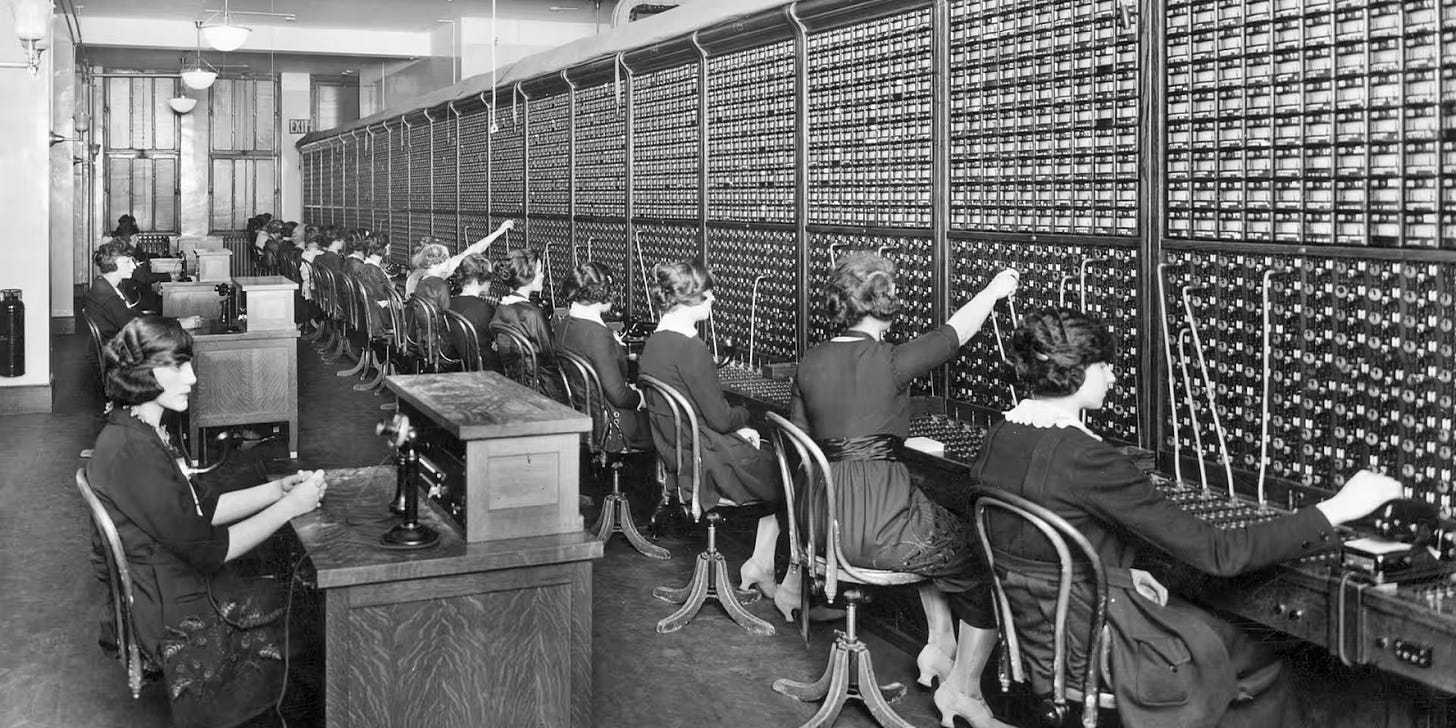

The same story has played out numerous times over the last several decades. Computers did automate tasks that people used to do manually. Bank tellers handled fewer transactions in person. Telephone operators disappeared entirely. Travel agents declined with the rise of online booking. Those shifts were painful for some on the losing side of these transitions. But the economy didn’t collapse under the weight of automation.

I watched this play out up close in the industry I know best. Digital tools overhauled political fundraising. Candidates could raise small-dollar contributions at scale without relying on traditional donor networks. Social media allowed candidates to build name recognition outside establishment channels. Candidates who gained fame this way came to hold an advantage over candidates who simply had establishment backing and little else — a real change from when I started out.

This had a dark side too. Social media fueled polarization and makes normal politics all but impossible.

But of all the ill effects of all this technology in the political arena, job losses weren’t one of them. There are still traditional fundraisers. There are still 30-second ads. Many of the people producing those ads either worked in the pre-digital era or learned at the feet of those who did. Even as an early digital pioneer, I now do more work on the traditional side of politics. Digital augmented existing workflows rather than replacing them. All the new money in the system — part enabled by digital, part enabled by Citizens United — was plowed into more activity at all levels of the political process. That inevitably means more people doing more things.

That pattern wasn’t unique to politics. Big Tech firms didn’t shrink into lean, hyper-efficient shells. They expanded. Google didn’t stop hiring because its core product — a search box that probably needed no more than a few hundred engineers to keep running — printed money. It invested in maps, cloud computing, mobile, YouTube, and AI itself. Amid the disinformation panic following the 2016 election, Facebook hired more than 10,000 fact-checkers and content moderators. You can debate the wisdom of that particular decision, which was fully unwound after the 2024 election. But it illustrates the point: new efficiencies didn’t lead companies to permanently reduce headcount to some theoretical minimum. They redeployed capital.

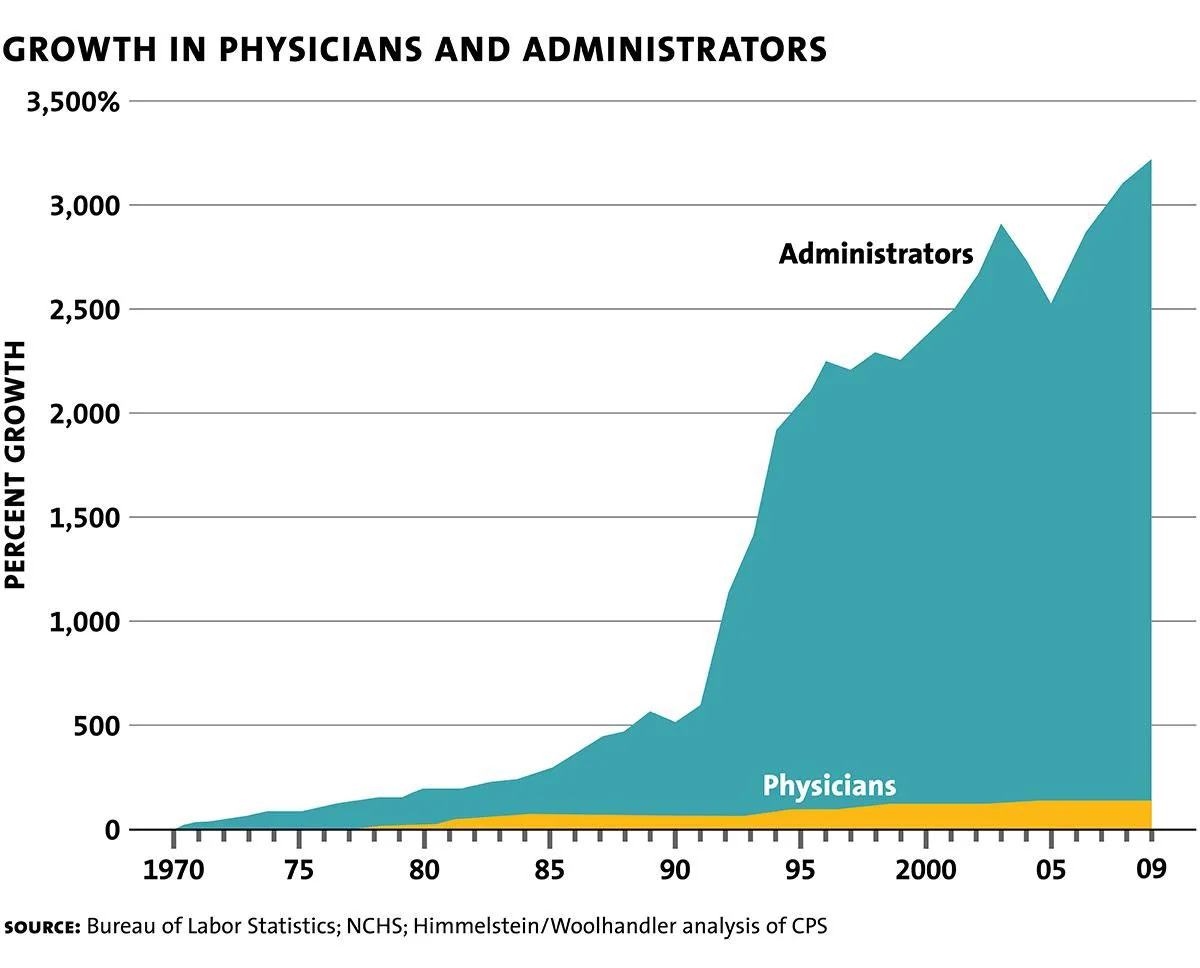

This is just how firms behave. They grow and experiment. They build new products and enter new markets. Even within large institutions like hospitals or universities, administrative layers expand rather than contract. The idea that big institutions will calmly accept higher margins and sit on them runs counter to decades of observed behavior.

AI won’t change any of this. If one function gets cheaper through automation, the savings get deployed somewhere — into new lines of business, new capabilities, sometimes speculative bets that don’t pan out. Or even into unproductive areas designed solely to influence public opinion or keep regulators at bay — the content moderation example above or the post-2020 DEI craze. Companies don’t aim to do the same with less. They aim to do more things with the same or more people.

What’s actually changing

I’ve spent months now in tools like Claude Code, Cowork, and Codex, and on a daily basis I have moments where I wonder if all the skills I’ve spent years cultivating in myself and others no longer matter — if everything can now be reduced to being a skilled operator of AI agents. These tools have completely replaced the need for me to ever write a single line of code. I can describe what I want and refine the output in a fraction of the time manual implementation would have taken.

But something important hasn’t changed. I still need to know what I’m trying to build. I need to define the goal and then evaluate whether the output actually solves the problem. AI can generate code, but it doesn’t decide what to build or which tradeoffs matter.

AI has automated the science of work but not the art. The fundamentals and subject matter expertise still matter. But everything else that was ancillary to that — manually writing the code that (maybe, sometimes) captures your intent, spending countless hours on tedious tasks like data cleaning — just magically disappeared.

The idea of a telephone operator manually connecting phone calls now seems archaic. So too will be the idea that you needed lots of software engineers to do things like build internal apps to replace something people were doing with Excel spreadsheets. This was never a good use of human talent. It was a friction tax on getting things done, and AI has largely eliminated it.

The worker most at risk in the transition isn’t the one with deep knowledge and good judgment. It’s the one whose entire job is performing a well-defined, routine task — the person whose output can be straightforwardly evaluated and replicated by a machine. That’s the telephone operator of the 21st century.

The knowledge worker who can direct AI toward the right problems is in a completely different position, and the gap between these two types of workers is about to get a lot wider. The person who understands a domain — politics, healthcare, finance — and can instruct AI to execute within that context will be able to do things that required big teams to do not long ago.

Intuitively, that should mean job loss, at least in the short run. But returning to the reality of how companies behave, there will continue to be some level of social pressure within firms to keep people employed, and when a firm is doing well, to expand employment. Most firms will continue to deploy capital, even to unproductive uses, not just sit on a surfeit of cash for lack of obvious opportunities.

And if we know anything from previous waves of tech enablement, it’s that new technology usually induces more work than it eliminates the need for. The upshot of giving corporate workers email wasn’t less paperwork — it was more time spent dashing off emails on phone screens at all hours of the day and night.

We’re already seeing this play out with AI in the public stats on the number of websites, the number of apps published to app stores, the number of code commits. It’s more output from the same number of people.

Much of this added output may prove frivolous and wasteful. The herd will be culled. Profits from the culling will be captured. But those profits will eventually be redeployed into investment (and employment) in other areas, some of which will initially be wasteful while other bets eventually pan out. And the cycle continues.

For me, AI doesn’t feel like a huge time saver. If anything, it’s the opposite. I’m spending more time trying to discover everything it can do to multiply my output and that of my team. The end result of that will hopefully be more things that get done and more people to do them.

🗺️ A density map of election results you should actually pay attention to

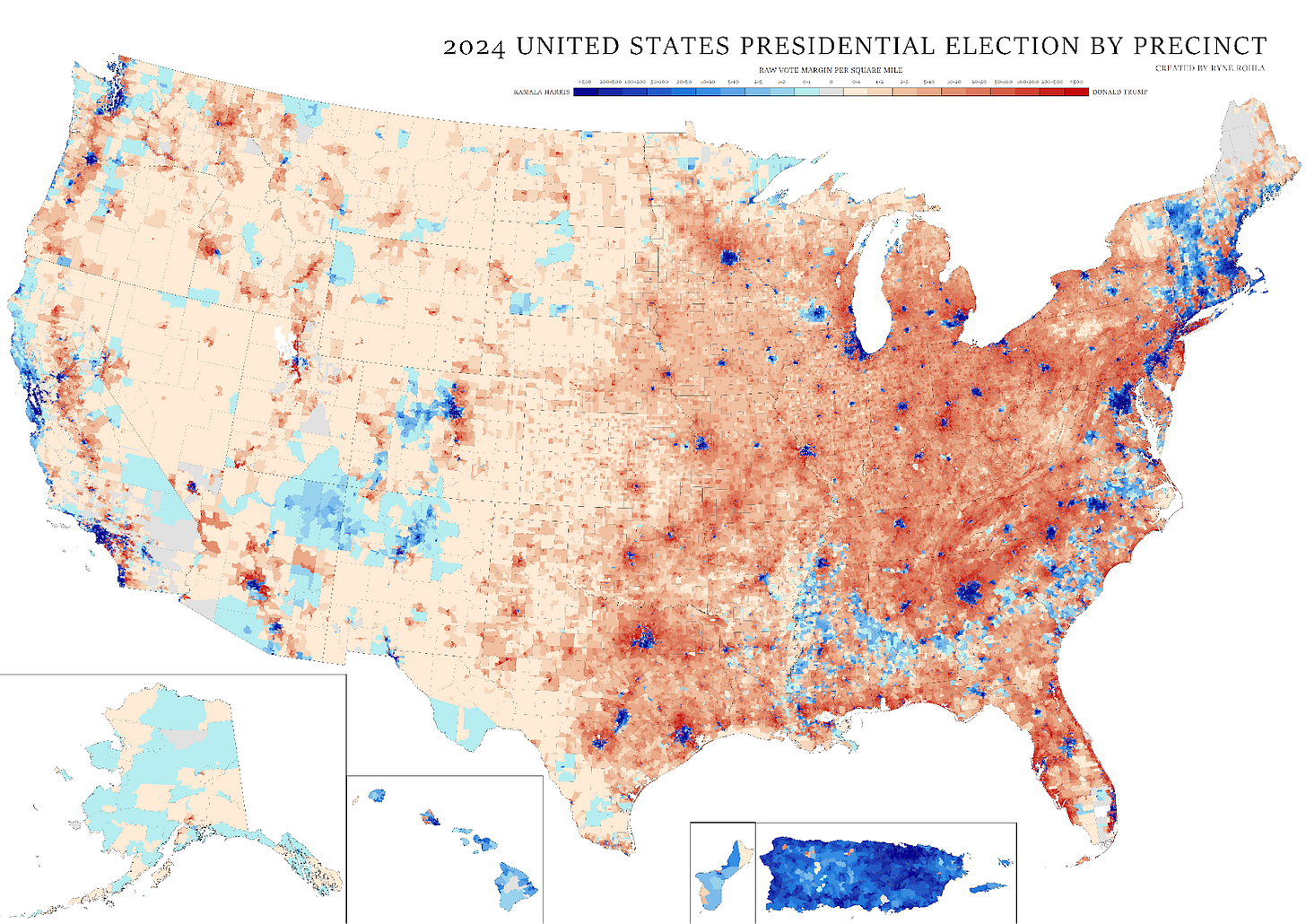

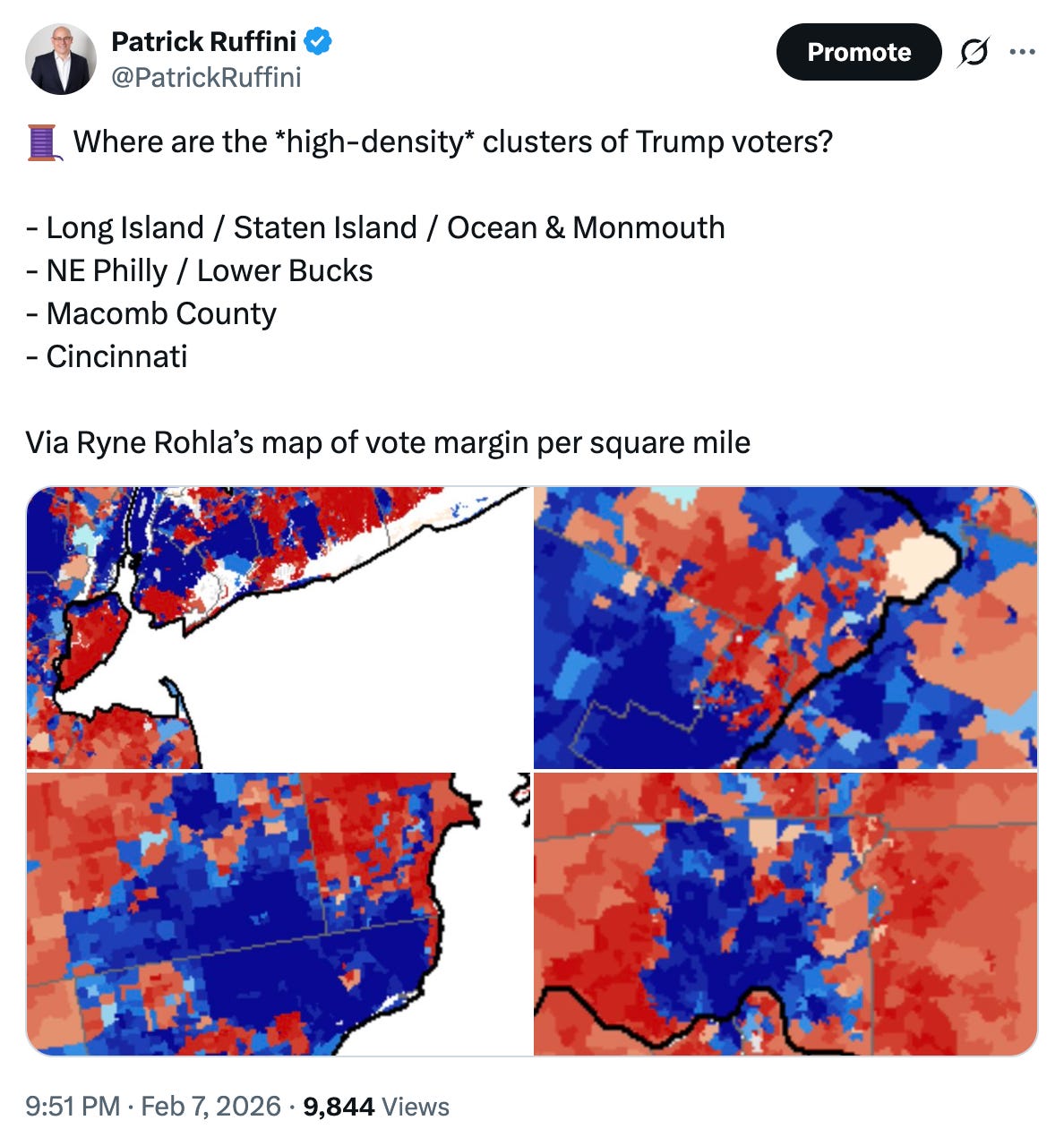

From cartograms to density-shaded maps, I’m not usually a fan of alternative types of election maps. But this insanely detailed map of 2024 election margins by square mile by Ryne Rohla is proving to be the exception. We all know that denser areas tend to be blue and more rural areas red. But what’s interesting about this map are the exceptions: look at the dense Republican areas (dark red) or the less dense Democratic ones (light blue). Outside of tribal areas, the Black Belt, and the West Coast, Madison, Wisconsin really is an outlier in playing host to a lot of Democrats in its rural outskirts.

If you’re a Republican seeking like-minded neighbors along with urban amenities, here’s a thread with 16 different places in the country you might consider.

🤖 How to save time after having that WFH baby

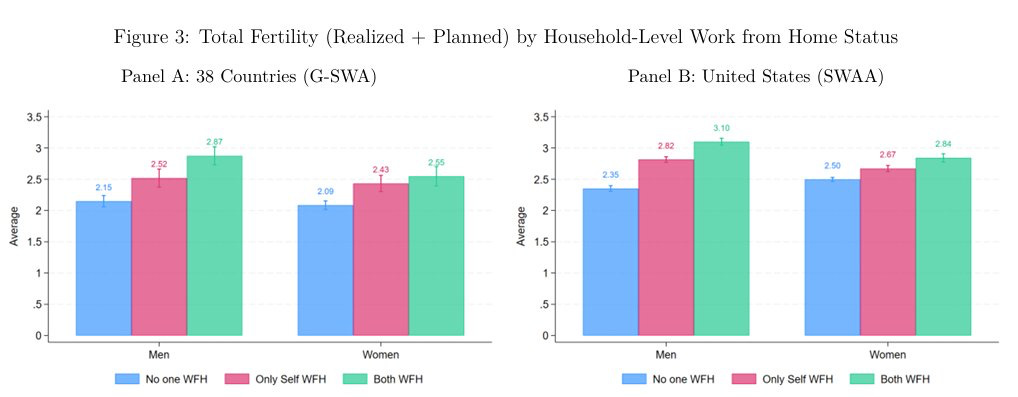

Increasing fertility is a notoriously hard nut to crack — even with direct cash payments to parents. So this new finding that both parents working from home increases fertility by a total of 0.32 children per woman is quite the eyebrow-raiser.

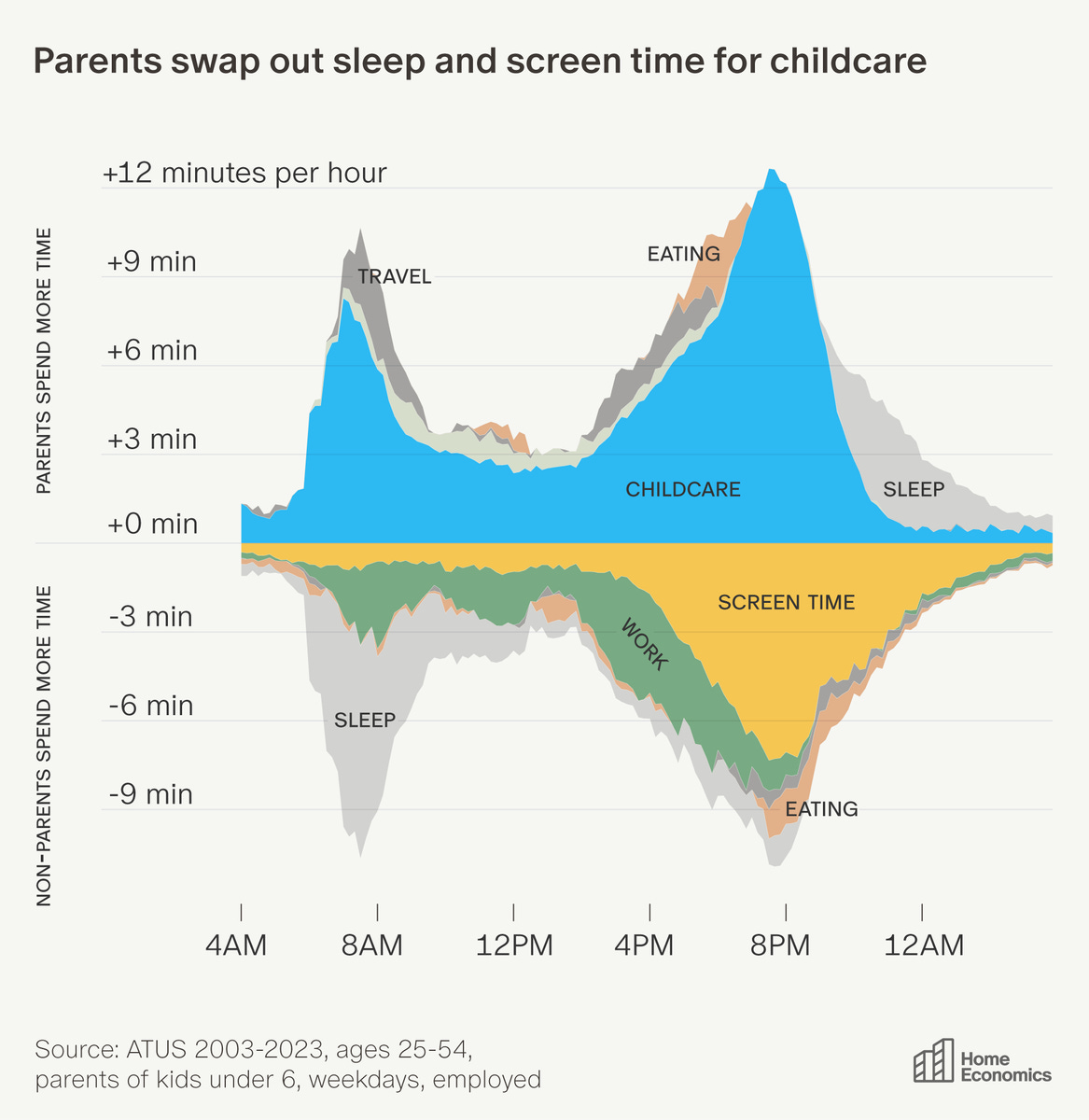

After you have those work-from-home babies, parents primarily fund their childcare hours by sleeping less and cutting screen time, rather than reducing work. Despite this tradeoff, parents report higher life satisfaction than non-parents. The biggest childcare demand hits in the evening (around 8PM), exactly when non-parents are unwinding with screens.

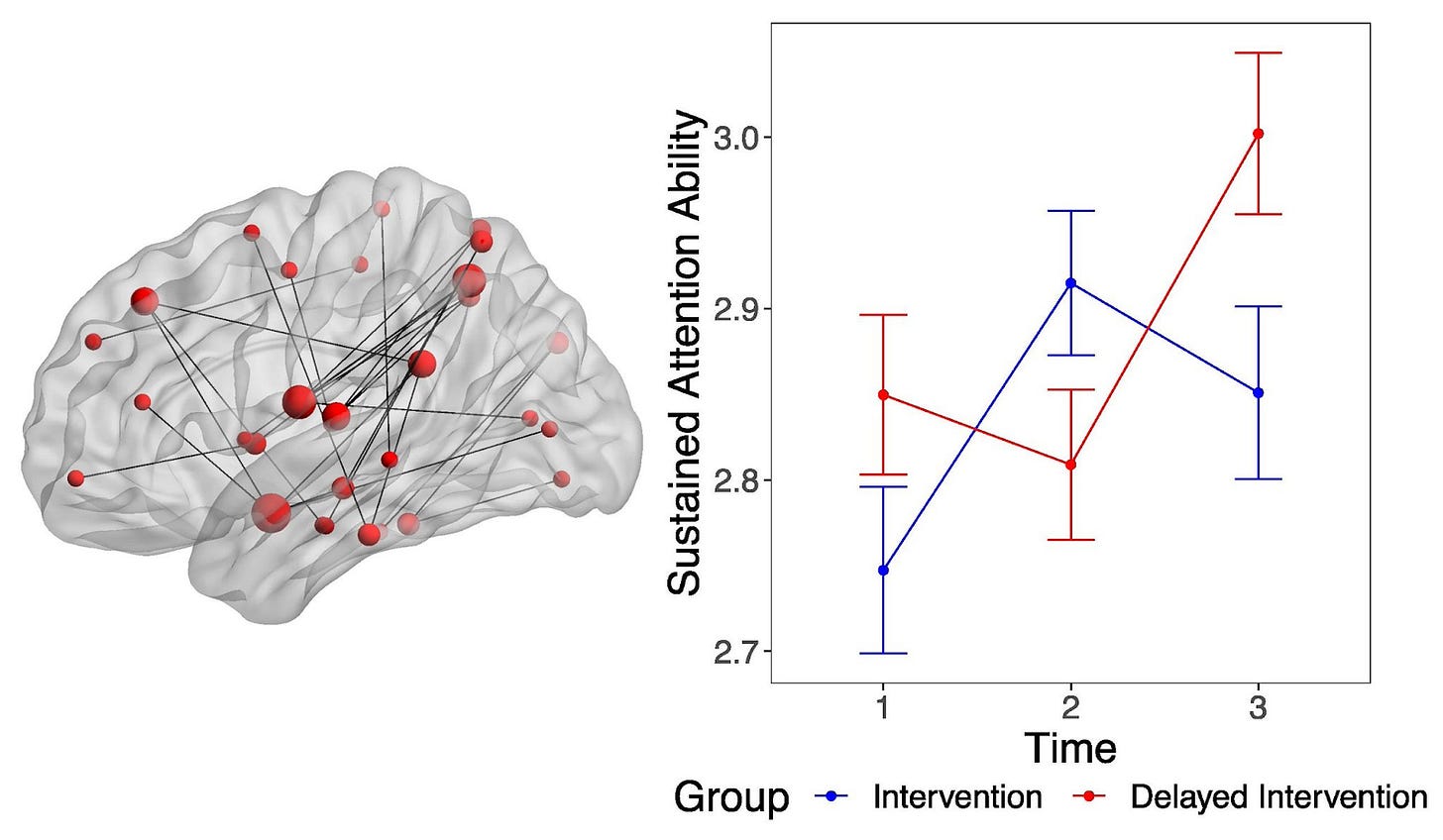

And cutting out screen time has lots of benefits even for non-parents. Just 72 hours without smartphones boosted sustained attention ability and activity in associated brain regions.