The midterm mirage

Why Democratic victories in 2026 could bury the lessons of 2024

When a party loses a presidential election, this prompts a period of introspection about what went wrong and forces the party to confront weaknesses swept under the rug during the campaign.

For the Democrats, this unfolded like clockwork following their 2024 loss.

But a few months later, this newfound openness to doing things differently has faded in the face of all-out opposition to Trump 2.0. In the U.S., midterm elections are a unique mechanism that squash heterodoxy and lock parties into sticking with their existing positions. The parties are thrown immediately back into campaign mode a few months after the election. That means the out-party quickly needs to maximize fundraising and enthusiasm from their base, which is usually at its angriest in the first few months of the opposing Administration’s term.

By favoring the out-party, midterm elections preempt the gnarly questions raised by the party’s last election defeat. And this false optimism carries through to the next presidential cycle.

If Democrats have a good election next November, you can count on their problems with Hispanic voters or young men to be memory-holed. Fans of the party’s existing strategy will argue that the current path works just fine. Just recall what happened after 2022: following a decent midterm, Democrats told themselves that Joe Biden was actually a viable candidate for re-election, that he was the only one who had beat Trump before and that he could do it again.

But the 2024 election would be fought on entirely different ground than 2022. Biden’s fitness was salient in a way it wasn’t when the party’s Senate and House candidates were front and center.

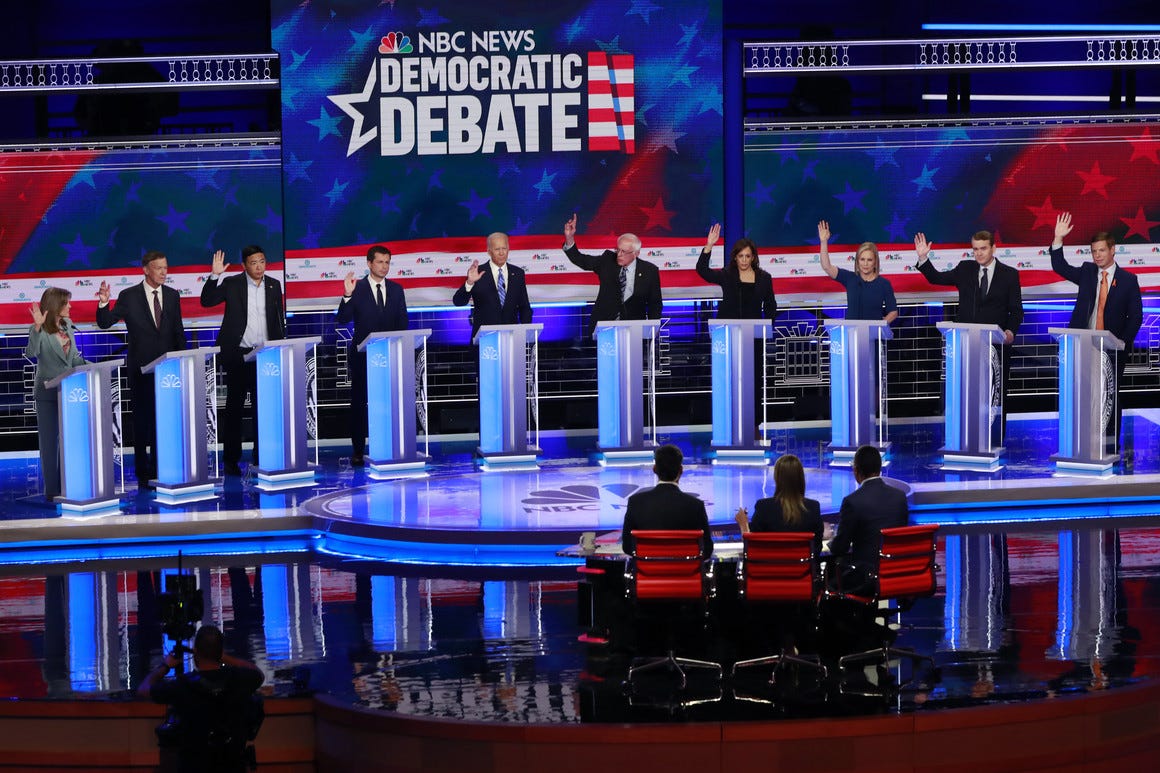

Or consider 2018, a smashing success for Democrats. The takeaway there was that all the party would need to do was take that Resistance mojo and double down on it for 2020. The party was on the upswing, and Democrats told themselves this meant a broad mandate for social change, not just a narrow repudiation of Trump. And so you got a race to the left to appease the groups, with hands raised on debate stages for decriminalizing border crossings and positions taken in favor of taxpayer funding for gender transition surgeries for illegal immigrants in prison.

We now know this created all sorts of downstream problems with traditional Democratic constituencies, problems invisible in the post-2018 euphoria but very apparent following the 2020 and 2024 elections.

Midterms are structurally different from presidential elections

The expected midterm results in 2018 and the idiosyncratic ones of 2022 sent precisely the wrong message to Democrats running in 2020 and 2024. Though Democrats did succeed in winning the White House in 2020, their misreading of too-rosy polls led them to assume that this year was an historic progressive moment, leading them to take extreme positions that presaged the losses with Hispanic voters we saw that fall. And the midterm result in 2022 led concerns about Biden to be swept under the rug, an even clearer misfire.

To state the obvious, midterms are generally not that predictive of what will happen in the next presidential race. Republicans proved a good deal stronger in both 2020 and 2024 than the previous midterm alone would have predicted.

Nor are midterm tsunamis are no more predictive of the next election than regular waves or ripples. Republicans got awfully cocky after the trashing they doled out in 2010, only to fall short in 2012. Bill Clinton had no trouble winning re-election after the Republican Revolution of 1994.

Parties do sometimes follow up a successful midterm with a presidential win the next cycle. This happened for Republicans in 2014 and 2016 and for Democrats in 2006 and 2008. But both sets of elections followed well-established cyclical patterns. The midterms are usually bad for the incumbent party, and the incumbent party usually loses the White House after two terms.

Midterm elections and presidential elections each happen on their own rhythm. Victory in one does not predict victory in the other.

Midterm success is all well and good, but a mere cyclical reaction to the party in power doesn’t solve the deep-seated problems exposed in the presidential year when the broadest set of voters participates.

Not only are the these two kinds of elections largely disconnected from one of other. In our current realignment, success in one can actively breed failure in the other (see, once again, “the groups” in 2020 and the delusions of the Biden Politburo in 2024).

The political divide in the 2024 election was expressed not only in shifting cultural and tribal alignments, but in turnout. It’s something you’ll hear me repeat often that irregular voters think differently than frequent voters. They’re less ideologically anchored and more “vibes”-driven. In our Political Tribes analysis, there are vast differences in the structure of political belief between people who always vote and the people who seldom vote.

In the end, it’s still all about low-propensity voters

Let’s think of the electorate as a line of people sorted by likelihood to vote. The first person in line is the person with a perfect likelihood of voting, and the last person has zero chance of voting.

In midterms, the line to get into the club gets cut off earlier in the night. The “VIPs” are a bigger share of the people inside. People who are more motivated get in, those who aren’t don’t. And if you’re the club owner in this scenario, in a midterm election you get a more stable and predictable clientele.

In presidential years, you get a lot more people who aren’t very interested in politics participating. Trump is optimized for this kind of electorate. His appeal transcends politics, mobilizing the previously apathetic—from steelworkers in 2016 to crypto bros in 2024. He polarizes people not just in ideological terms, but along lines of adherence to norms and procedures. The club VIPs who know all the rules of politics tend to be turned off by him, and those left standing outside tend to like him. This is the basic inversion of who high turnout benefits that’s been much talked about. In 2024, we saw special elections no longer be a good signal of the fall outcome: Democrats did a lot better with this high-propensity voter than they did with the full electorate.

The shifts in the fall of 2024 were all about low-propensity voters. Not just Hispanics and other minorities, but young voters, non-college voters, unmarried voters, low-income voters. When these characteristics all compounded in the same person, the shifts to Trump were bigger, in a kind of pro-MAGA version of intersectionality.

But these people don’t reliably vote. And their loyalties might be temporary anyway, so even if they did vote, it’s not clear who it would help.

That not only changes the kind of voter you’re talking to demographically in a midterm or presidential cycle, but it changes the issues you talk about. Democracy and abortion were salient issues in 2022 but not 2024 not only because the agitating events were fresher in memory (January 6th, Dobbs), but because they selectively motivated high- and mid-turnout partisans. Immigration serves a similar function on the right: the most ideological and highest-turnout Trump voters care about it a lot more than irregular Trump voters. Caring about the cost of living, the dominant issue in polls, is almost adverse selection for actually turning out in a midterm or special election. Low turnout is in fact a statistically significant predictor of whether or not you care about the cost of living. Because the constituency for it isn’t active and doesn’t vote as much, concrete solutions to it get short shrift from politicians on both sides in policy terms. And much the same is true of the related issue of housing costs.

Running a base mobilization strategy can work in midterms but in presidential years, usually gets canceled out quickly by an influx of low-information and more persuadable voters motivated by an entirely different issue set.

And that’s why, in recent years especially, we’ve seen whiplash every two years when it comes to which party overperforms its baseline. In 2016, it was Republicans, in 2018 Democrats, in 2020 Republicans, in 2022 Democrats, and in 2024 Republicans. Politicians think they can apply the lessons of one election cycle to the next one, when in fact the opposite is more likely true.

While many Democrats sincerely want to change how their party is perceived by low-propensity voters, all the incentives going into and following the midterms are lined up against them. The better Democrats do in the midterms, the more that arguing for a change in direction makes you the skunk at the garden party.

If you actually pay attention to Democratic messaging, it's indeed largely about prices, Medicaid, and broken Trump promises — which doubles as base motivation. It's MAGA that seems to want to talk about trans athletes, universities, and Sydney Sweeney.

Democrats need to shift their strategy and it is possible that a strong midterm performance would delay that.

But the shift in strategy that’s necessary is to compete in more states and more districts.

I don’t pretend to know what 2028 will be like, but the most predictable result will be antipathy to Trump and Republican submission to him leads to a small Democratic victory. But winning the Presidency 50% of the time isn’t enough for Democratic goals because we’re not competitive in too many states and therefore the Senate map is always rough. Not to mention state legislatures and governors mansions.

The choice shouldn’t be about juicing the base or chasing low propensity voters. It should be about how to get at least 75% of America to not hate when you win and maybe even consider voting for you when the other side throws up a corrupt or incompetent official. That’s how you can compete everywhere and enact legislation with some legitimacy.