The myth of MAGA isolationism

Polymarket insiders, the Claude Code moment, AI as the new crypto, the 2020s population race

No. 386 | January 9, 2026

🇺🇲 Why “America First” doesn’t mean what you think it means

The rise of Donald Trump was supposed to represent a break from the hawkish foreign policy that has defined the Republican Party since the Reagan presidency. Trump’s criticism of the Iraq invasion in the 2016 primaries heralded a new populist era where the GOP’s old foreign policy wisdom was thrown by the wayside. Many neoconservatives seemed to think so: they were the first to exit the GOP after Trump’s ascendancy and prominently endorsed Trump’s opponents, most prominently the late former Vice President Dick Cheney and his daughter, Liz.

And yet the first year of Trump 2.0 has been surprisingly Cheney-esque in its foreign policy: strikes on Yemen in the opening weeks of the administration, U.S. military strikes inside Iran, and now the capture of Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro.

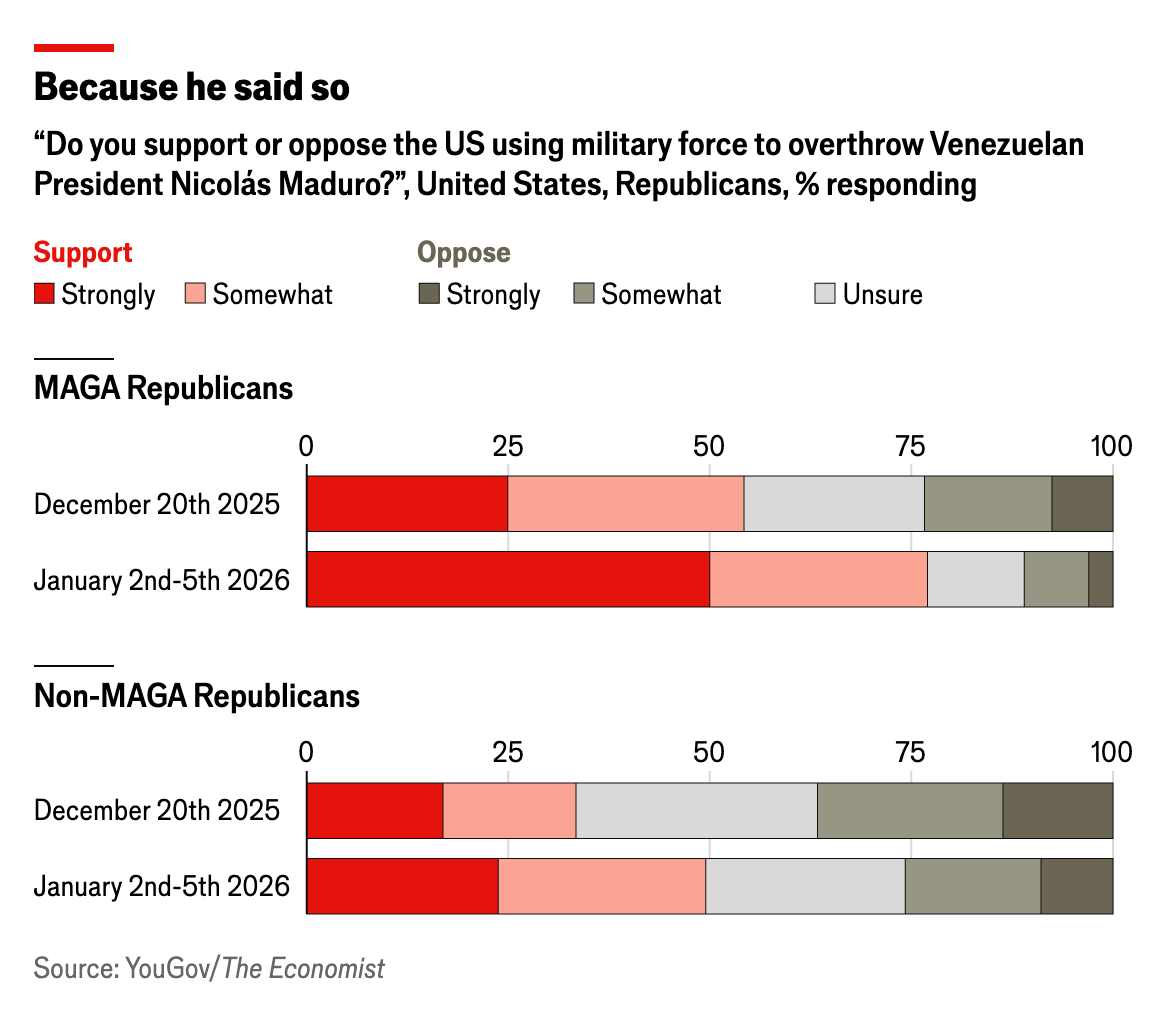

Republicans have rallied behind the operation, with support among MAGA Republicans stronger than non-MAGA Republicans.

…