The trouble with modeled partisanship

One more caveat when trying to read early-voting tea leaves

We are now in early voting season and the fight-du-jour is whether and how to use “modeled partisanship” in interpreting early vote return and new voter registration data, particularly in states where voters don’t register by party. In the battlegrounds, this includes Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Tom Bonier, former head of the Democratic data firm TargetSmart, has been the main defender of the use of modeled partisanship, posting rosy numbers about voter registration trends favoring Democrats because TargetSmart’s model suggests they should be Democrats based on their demographics. This portrait often contradicts the hard evidence coming from party registration states that show Republicans gaining ground pretty much everywhere in registration.

I founded a company that builds these sorts of models, so I think I can offer some context about how voters are labeled as modeled Democrats and modeled Republicans, and what the limitations of this are.

The long-and-the-short of it is that the modeled party variables distort actual partisan preferences in the electorate and don’t represent the actual survey data used to build these models. The modeled party field skews too Democratic in most states.

TargetSmart doesn’t release data on what modeled partisanship looks like in every state, but nonpartisan L2 does. And if you look at the TargetEarly and the L2 early voting dashboard, the modeled partisan composition of roughly the same early voters in the same states are each within a few points of the other, so we can infer that TargetSmart’s modeled partisanship scores of the overall electorate are roughly in line with L2’s.

Ok, with that out of the way, what are L2’s modeled party estimates in some key non-registration states?

In Georgia, modeled Democrats are 43%, modeled Republicans 28%.

In Texas, modeled Democrats are 46%, modeled Republicans 38%.

In Virginia, modeled Democrats are 49%, modeled Republicans 33%.

In Ohio, modeled Democrats are 32%, modeled Republicans 32%.

Adding in modeled party to party registration and past primary voting history, Democrats go from what should be a 3.5 point lead using the hard data alone to a 7 point lead on Republicans nationally.

Now, the problem with using these figures to benchmark early voting performance starts to come into clearer view. In most states where you need to rely on modeling, this metric vastly overstate the Democratic vote, often by double digits. In many cases, like Georgia and Texas, the partisan lean on the voter file is inverted from what the politics of these states are in reality.

Modeling can also be too bullish on Republican performance, for instance in Minnesota, where Republicans have a lead of 4 points — 38 to 34 percent.

I want to be very clear that none of this is to disparage L2’s modeling. In fact, they’re the voter file company I primarily use.

The problem is not with the underlying data, but with the misuse of the modeled party field by analysts when trying to decipher trends from early voting.

To see why, it’s important to understand how the modeled party field is built: a company runs surveys and assigns each person on the voter file a 0-to-1 probability of being a Democrat, Republican, or unaffiliated. Factors like race, gender, and past election results in their area are taken into account.

If your score on the Democratic model is much higher than the Republican model, your modeled party is Democrat.

Now, the distribution of scores turns out to matter a lot. If Democrats in a state are easier to identify than Republicans, it will classify people as Democrats more easily than Republicans. Examples of groups easier to identify as Democrats are African Americans, people who live in big cities where Democrats win big, and young women.

That’s how you get too many modeled Democrats in large, diverse states like Georgia and Texas: all Black voters and the lion’s share of Hispanic voters will tend to be classified as Democrats, with plenty of false positives, when in a registered party state, no more than 70% of registered voters in a group would be Democrats. No Republican group is as easily identified, so they’ll tend to be modeled as unaffiliated more often.

If you’re an L2 or TargetSmart client, by the way, this is what you want these companies to do. The vast majority of the clients for this data are political campaigns who are using this data to target voters. They need a simple heuristic to tell them which people to go after without having to fiddle with the model scores themselves. But this is not as good a metric as a pollster or statistician would want, because it doesn’t reflect the true distribution of Republicans and Democrats in the electorate.

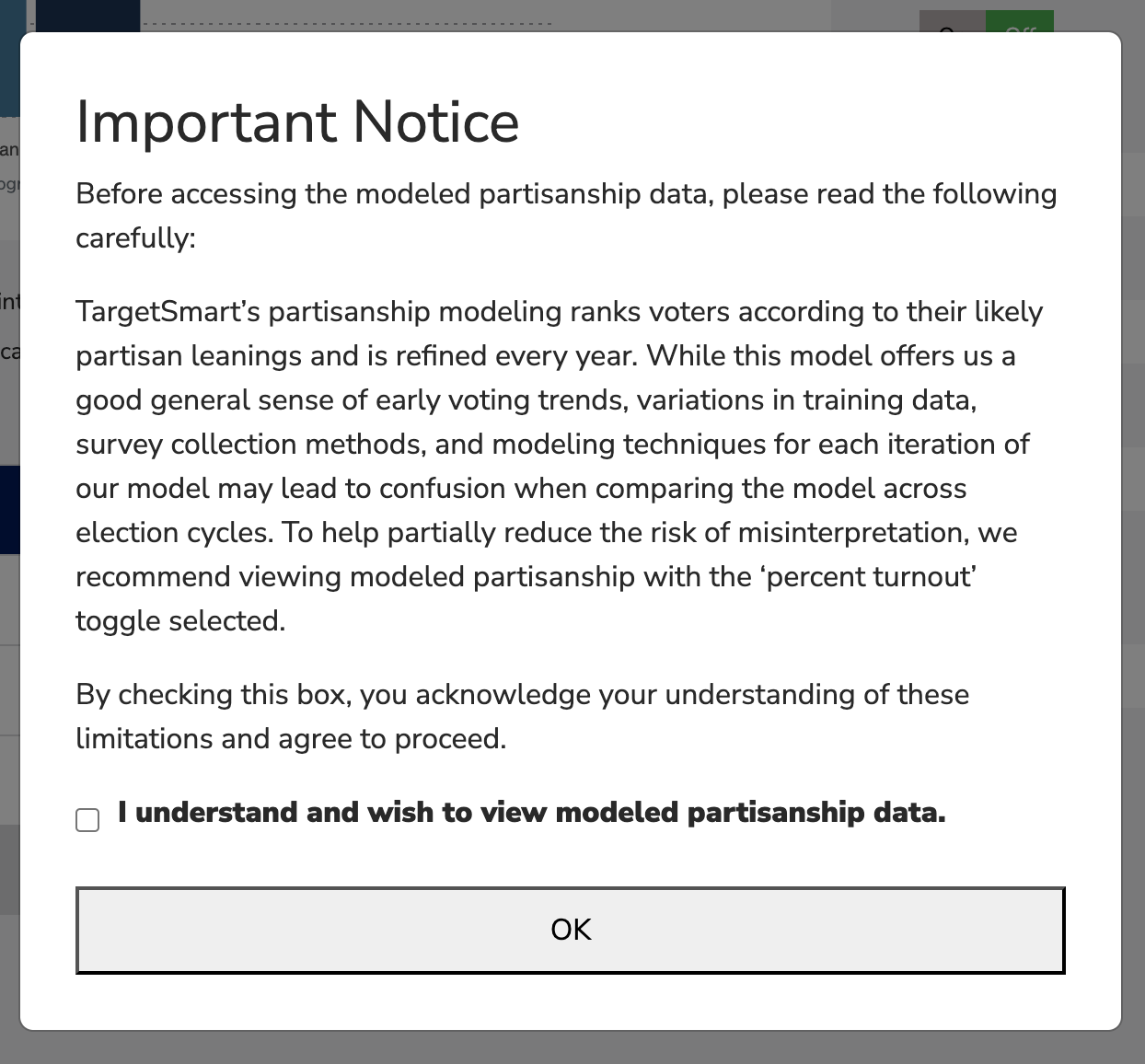

Even TargetSmart, the source of much of this overly-rosy Democratic data, features a big fat disclaimer when you try and toggle the modeled party field on its dashboard.