Where Trump and Harris could outperform across the seven battlegrounds

Despite nationalized trends, regional variation still counts for a lot

Pretty much all the places where most people have college degrees swung left in the 2016 and 2020 elections. And the places with lots of working class whites, especially in the Rust Belt, swung right. Heavily Hispanic areas swung right in 2020, for the most part across the board.

Nationalized trends give us the idea that we are moving towards a future where regional differences will give way to a nationalized politics organized around the diploma divide. In this story, it doesn’t matter much if you live in New York or Texas. If you’re the same kind of person living in either place, you’ll have the same politics.

Education matters a lot more than it did. But the focus on shifts loses sight of the fact that 2012-20 shifts happened in places where college graduates and working class voters started off on very different baselines. Staunchly Republican suburbs moved left just as much as ones that were pretty Democratic to begin with. Only where it was mathematically impossible for Republicans to grow further, such as among rural Georgia whites, did the existing level of Republican voting serve as a constraint on these trends.

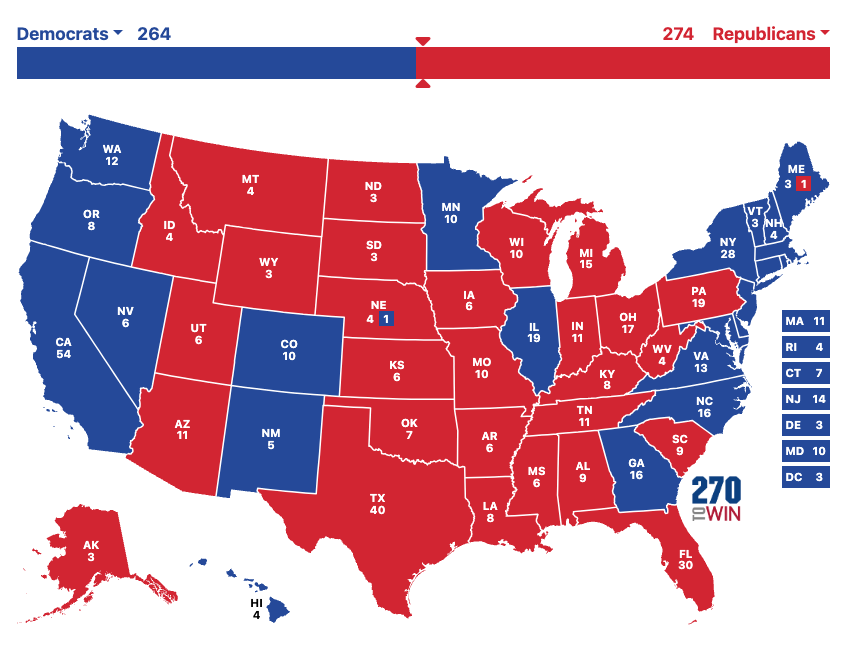

To see just how much of a difference regional differences still make, I built a model of how the battleground states “should” have voted in 2020 if all we knew about them was their demography and population density. And some states are voting double digits to the left or right of where demography suggests they should be voting. Wisconsin in real life is 14 points to the left of demographic expectations, and Georgia 14 points to the right.

And if these states voted as national demographic trends suggest they should, Republicans and Democrats would trade their relative advantages in the Rust Belt and the Sun Belt—though Pennsylvania and Arizona would remain very close.

The most dramatic gaps, those in Wisconsin and Georgia, come down to basic demography: Wisconsin has many more whites and rural voters than the rest of the country, but votes to the left given what we would expect based on those factors alone. And Georgia has very similar demographics to Maryland, with a highly urban population and 3-in-10 voters who are African American, but Maryland will vote Democratic by well north of 20 points while Georgia remains competitive.

This might be a good time for common sense to enter the chat. Of course Georgia votes to the right of how it “should” vote: it’s a southern state where the whites are more conservative than they are in Wisconsin, with little history of racial strife and a progressive movement dating back to the early 20th century.

But not only does north-south regional variation matter a lot: so do differences between states in the same region. North Carolina would be a far less Democratic state than Georgia, at D+3, compared to Georgia’s D+14. And Wisconsin would be well to the right of Michigan (R+4) or Pennsylvania (R+1).

The 2024 results will obviously look nothing like this, but running this thought experiment can help us break down where the parties have longer-term upside, and where they might be poised for a breakthrough this fall. Existing political performance — a majority party having more more room to fall and a minority party more room to gain — is one factor that can cause states to shift over the long haul. It’s no accident that Trump’s 2016 gains came mainly in places where there were lots of working class whites who voted for Obama: mathematically, there were more voters available to flip.

What else can cause states to vote to the right or left of where demographics says they “should” vote, and which parts of these states are the most “out of step” with national trends, indicating possible upside for Trump or Harris?